War of the Worlds (review)

War of the Worlds (review)

What can I say. If it wasn’t for H.G. and his nightmarish vision of apocalypse, I might have become some sort of illiterate dummy.

As it was, when I was about eleven, I read below par. It didn’t interest me, I didn’t care, it was boring, yada. Then my mom (bless her heart) sat me down every night and made me read for 30 minutes. Didn’t matter what. The TV guide, the back of a cereal box, anything as long as it had words on it.

So I read a little of this and a little of that from the school library. Then one day I fetched up a copy of “War of the Worlds” illustrated by Edward Gorey (how could I miss it with its purple-sky cover – Air-Sea rescue would spot it). Honestly, I think I was captivated by the tiny little flaming people running about a tripod’s feet on the back cover. Pretty creepy. So I sat down and started to read.

For those of you who have never read this classic, heard the infamous radio broadcast, saw any of the hack-job movies, or have lived with a bucket over your head, WOTW (as I affectionately call this book I’ve read over twenty times) is the classic science fiction “role reversal” tale. In his time, Wells was disturbed by British Imperialism, particularly the extinction of the Tasmanians whom the Empire had wiped out in over a bloody half-century. He wondered what it would be like if our race (and his nation) suddenly experienced the same pitiless extinction.

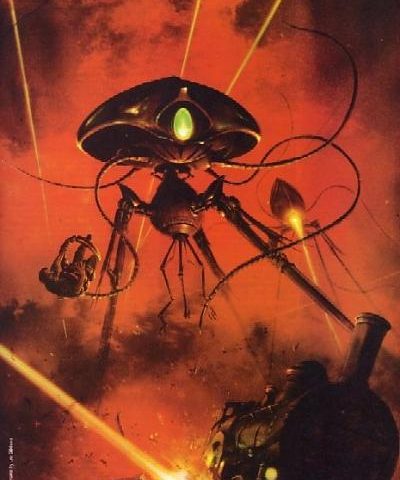

And so the Martians arrive in their cylinders, literally shot to Earth from some massive Mars-based gun. Heedless of the danger, the populace and the military dither. And then emerge the fighting machines, huge tripods that stride about with their heat rays (you japanimation robot freaks should perk up at this, for what is a tripod other than massive power armor for a tentacled being?) There are a series of grim battles, the gassing of London, the horrible flight of its inhabitants, the Empire’s final act of defiance (alas, brave Thunderchild), and then its the end. England has fallen. The second part of the book finds the narrator stumbling about, growing weaker, hungrier, depressed, driven to the point of suicide. Then, “after all the devices of mankind had failed”, the Martians die from bacteria (which they’d removed from Mars eons ago).

The true brilliance of this book was the remarkable things it said to a child in his early teens, one weaned on the principles of western storytelling and culture. Each night, as I burrowed deeper into the science-poetry of Wells (for his writing is nothing short of beautiful), my youthful outlook was burnished by the cold realities of the invasion. To wit…

1) Humans are decent, thoughtful, and communal: Actually, the first fatality of the war is a fellow who is butted into the pit by the gawking mob, to be eaten alive. And later, when the heat ray sweeps the common, that same mob (now fleeing) crushes a woman and some children in a narrow spot in the road, where they are left to slowly die in the darkness. Wow.

2) Heroes act heroically: Our hero, when the heat ray is first employed, gaps like a rube. Only the fact that the Martians decided they’d shocked and awed enough and shut off the beam kept WOTW from being a very short story. The hero panics, frets, dreams of revenge, and pretty much reacts in very human ways through the entire book. In that, he was the first real character I ever encountered as a young reader.

3) Strategy and resolve will overcome technology: The humans set up a nifty artillery ambush at Weybridge and splash a Martian “to the four winds of heaven”. Before falling back, the Martians really let loose, burning the town, the defenders, the refugees, everything down to the bedrock. Later, in the defense of mother-city London, the humans employ every battery they have, ready to stand or die. The Martians simply gas them like wasps without breaking into a sweat.

4) Last stands always work: The ironclad Thunderchild makes a heroic defense of a refugee ship. It clobbers two Martians. Hope soars! Then it’s sunk. Along with rest of the fleet (implied). And then the Martians fly overhead in their new flying machine. Its over, folks. Please disconnect your speakers before driving to the exits.

5) Gott mit uns: Not only do churches get blasted all over the place (a tripod even falls over one at Shepperton), it’s the curate who gets high marks for whining, whimpering, and finally going into such a state of loud rapture he’s put down with the blunt end of an axe. You’re not suppose to put this in books, are you?

6) The vision of tomorrow: The visionary (the artilleryman, a practical blunt fellow) offers the hopeless narrator a vision of the future, of a brave new world that will ascend to challenge our Martian overlords. The problem is, he’s too much of a lazy lout to do it. I love the line about “the gulf between his dreams and his powers”.

7) The hero will prevail: Actually, the hero is on the verge of suicide when he realizes that the Martians are no more.

If any of you Harry-Potter-happy-ending fans are still with us, you are probably wondering why anyone would enjoy such gritty reality. Well, that’s just it. To a young child on the tail end of the happy, prosperous fifties (actually, it was nearer the end of the sixties and the world was already changing), it was like a breath of fresh air. It’s the thrill of the thing, like getting on a roller coaster that has never been tested, with no assurance of inspection or insurance. Characters die. Cities burn. The human race is driven to extinction. With this bleakness comes a freedom. The story comes with no guarantee. There might not be a happy ending. Conventions do not exist. Clichés have no anchor point.

In the final chapter we travel with the narrator by train, looking out the window at the slowly healing land, the wheels of the carriage rattling across the newly-lain rails, reflecting on our place in the universe (no longer lounging on our throne atop everything). And we, as readers, can sigh and reflect that we have truly been there and back again, that we have survived, and that we will carry this story with us, always.